(Shaman Showman - part 4)

|

| "Dancing Sorcerer" After Henri Breuil's drawing. |

“The oldest religion of which we have any secure knowledge

is the shamanism of the late Old Stone Age (Paleolithic) as we have seen it

depicted in the caves of southern France and northern Spain.” (Weston LaBarre.) Further, “Nothing justifies the supposition that, during the hundreds and thousands of years that precedes the earliest Stone Age, humanity did not have a religious life as intense and

various as in the succeeding periods.” (Mircea Eliade.)

Research and deepened understanding of early religious practices reveals the riches of the religious experience of these ancient human systems. They were in no way inferior in their ability to supply answers to big philosophical questions, to control the dangerously random processes of nature, to strengthen community bonds, or providing real healing powers in times of sickness.

Research and deepened understanding of early religious practices reveals the riches of the religious experience of these ancient human systems. They were in no way inferior in their ability to supply answers to big philosophical questions, to control the dangerously random processes of nature, to strengthen community bonds, or providing real healing powers in times of sickness.

|

| 12000 yo cave painting, Trois Freres, France |

From the furthest recesses of time our ancestors put their trust in shamans with spiritual and bodily needs. For the shaman was not only priest but also medicine man. Today this seems very strange indeed, since doctor and priest are two very separate occupations. Each belonging to fundamentally different ideological systems, namely science and religion. In these ancient times though, such distinctions were yet to be made. It is interesting here to note that, at root level, these sprung from a similar source.

“In a mysterious world full of unknown dangers like death, disease and other disasters, the shaman is the man who claims knowledge and power over these frightening mysteries that the ordinary man manifestly does not have. Clinically, we might view the shaman as a paranoiac, in his claims to omniscience, omnipotence and omnibenevolence. And yet, since these are what his clientele demand of him, these are what the medicine man must purport to provide.” (LaBarre)

All this was the shaman's obligation. Since early

man placed their faith in shamans we must ask: What did shamans do to deserve

this trust? What powers did they wield? And how well did it work?

Shamanism was practiced worldwide, from Europe to America,

Africa to Mongolia, and Brazil to Japan. This enormous distribution might certainly be taken as an

indication of its efficacy. It did what it set out to do effectively enough for

the practice to be almost universal.

What powers did they wield?

According

to Melbourne Christopher, one of the oldest and most performed Native American

mysteries was a ritual know as the shaking tent. It was an important and often

performed shamanistic ritual amongst the North American Cree Culture. It played an important role in the yearly cycle of harvest and other

ritual activities of the Innu people of Quebec and Labrador.

“It was not

only an important method of direct communication with the caribou and other

animal masters, as well as with Mishtapeu and cannibal spirits, it was also a

source of amusement. The shaman used the tent to look into the hidden world of

animal spirits, and to make contact with Innu in distant groups.” United Cherokee Nation.

|

| Shaking tent ritual in progress. |

“As soon as

the Kakushapatak stuck his head in the tent, it would start to shake violently,

indicating that the officient had been joined by a spirit, usually Mishtapeu

who helped him communicate with the other spirits."

in his book "Magic and Meaning," magician Eugene Burger gives an interesting description of this ritual

performed in an unusual setting:

“At Leech

Lake, Minnesota, in the 1850’s, an Ojibwa shaman was offered a hundred dollars

if he could successfully demonstrate this talent. He was securely tied,

observed by a committee of twelve, including an Episcopal clergyman, and placed

in his tent, which began to sway violently. Strange sounds were heard. The

shaman shouted that the rope could be found in a nearby house. When one of the

group was sent to the house, the knotted rope was found. In the tent, the

shaman was found peacefully smoking a pipe.” According to Christopher “The

committee – now eleven, the clergyman having fled, crying that this was the

work of the devil – agreed unanimously that the hundred dollars should be paid

at once.”

This

challenge was no ordinary setting for shamanistic activities, but nonetheless, the demonstration must have been formidable. Despite their intention of discovering the trickery involved in the shaking tent ritual, the critically minded gathering of men found no evidence of deception. A crowd of firm believers would then be even less likely to do so. From a magician's point of view, this would be described as a successful performance by a master of his craft.

We have information from ethnologists and anthropologists about the attitudes of both the audience and the performers of these events. Not surprisingly, it is described both as magic and as trickery. Some of the audience believed wholeheartedly it was magic, whilst others could see how the shaman had used certain hidden techniques to shake the tent. Again, the ritual’s wide distribution and popularity is a testament to its efficacy. Regardless of one's attitude towards the mechanics, the ritual had real value for communities across the globe. Real magic or not, the power was undoubtedly a force to be reckoned with. Indeed, the ritual was banned by law for 70 years.

“In the

1880s, missionaries and Indian agents helped ban and suppress religious

practices of First Nations across Canada, including the shaking tent Ceremony

practiced by the Blackfoot, Cree, Innu, and Ojibwa, as well as the sun dance.

The bans weren't lifted until 1951. Some native people risked jail to preserve

their spiritual beliefs. Because of their efforts many of these ceremonies are

practiced today.” (CBC.)

|

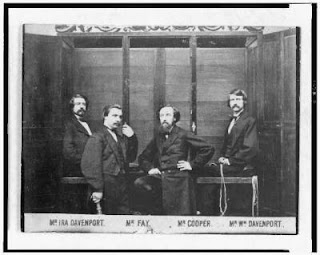

| Davenport brothers by their spirit cabinet. |

The

description of the shaman's performance of the shaking tent seems to me to be

virtually indistinguishable from the activities of the magicians that brought

on the Spiritist movement of the late eighteen hundreds. The Spirit cabinet was a staple of magicians, or mediums, as they called themselves. In this presentation the medium was tied up inside a cabinet or behind a curtain, and musical instruments were placed with them, but out of reach. Once the cabinet or curtains were closed, spirits were called upon and music would be produced. When the curtains again opened the medium was still tied up.

This escape act, for that is what it was, served as proof of the performer's ability to summon and communicate with spirits.

As with the Native Americans, the attitudes amongst magicians, mediums, spectators and believers varied greatly. Both these examples garnered believers and skeptics. Whilst people like Harry Houdini exposed spiritualists and mediums as fraudsters, countless others found peace through messages rapped out on tables and tambourines played behind curtains. Whatever the techniques used, the effect on believers was real.

This escape act, for that is what it was, served as proof of the performer's ability to summon and communicate with spirits.

As with the Native Americans, the attitudes amongst magicians, mediums, spectators and believers varied greatly. Both these examples garnered believers and skeptics. Whilst people like Harry Houdini exposed spiritualists and mediums as fraudsters, countless others found peace through messages rapped out on tables and tambourines played behind curtains. Whatever the techniques used, the effect on believers was real.

Another

shamanistic practice described by Mircea Eliade in "Rites and Symbols of Initiation" (1965) is an initiation into manhood of a tribe of Australian

Aboriginals.

|

| Central Australian bull roarer. |

The

boy on the cusp of manhood is instructed about a bad spirit who likes to eat

little boys and then tries to revive them. With this in mind, the boy is taken out

into the desert where a roaring unearthly sound appears in the distance and the

boy is told it is the very bad anthropophagic spirit that at any moment will

eat him.

The men place the boy under a blanket as the sound comes closer. When the sound is right on top of the boy an elder reaches under the blanket and uses a hammer and chisel to knock out one of the boys teeth. On the last day of the rite a fire is lit and the boy is put under the blanket again as the strange sound appears from the dark. It gets louder and louder as it comes closer. When the boy has become suitably terrified, the blanket is removed by the elder and the boy is initiated into the secret knowledge of the ritual. They reveal that the true source of the sound was a bull roarer, a carved flat wooden stick on a string which is spun around over head and in the process it creates a very peculiar sound. The stick whirls around on the end of the string not unlike a propeller of a plane and the sound of it tearing the air is surprisingly formidable. Once the boy is shown the bull roarer it is burnt in the fire and with this the boy is a man.

I find it quite interesting that the completion of the ritual is the revelation of the deception. Revealed in the correct manner, this does not appear mundane and deflated, but a necessary tool, instilling a very particular and powerful state of mind in the boy.

“The shaman’s deception may in this sense be the ‘necessary lie’ that brings others to trust in healing powers – and, thereby contributes toward bringing about the healing experience,” notes Eugene Burger.

The men place the boy under a blanket as the sound comes closer. When the sound is right on top of the boy an elder reaches under the blanket and uses a hammer and chisel to knock out one of the boys teeth. On the last day of the rite a fire is lit and the boy is put under the blanket again as the strange sound appears from the dark. It gets louder and louder as it comes closer. When the boy has become suitably terrified, the blanket is removed by the elder and the boy is initiated into the secret knowledge of the ritual. They reveal that the true source of the sound was a bull roarer, a carved flat wooden stick on a string which is spun around over head and in the process it creates a very peculiar sound. The stick whirls around on the end of the string not unlike a propeller of a plane and the sound of it tearing the air is surprisingly formidable. Once the boy is shown the bull roarer it is burnt in the fire and with this the boy is a man.

I find it quite interesting that the completion of the ritual is the revelation of the deception. Revealed in the correct manner, this does not appear mundane and deflated, but a necessary tool, instilling a very particular and powerful state of mind in the boy.

“The shaman’s deception may in this sense be the ‘necessary lie’ that brings others to trust in healing powers – and, thereby contributes toward bringing about the healing experience,” notes Eugene Burger.

“Initiation into adulthood can be

equally an initiation into spiritual deception. What is being worked over in

the boy is their belief about spiritual reality.” (Robert Neal) The elders introduce the boy

to a means of creating a religious experience through a very particular form of

deception not meant to further the shaman's interest, but aimed to benefit

others, to give them a very particular insight.

If one is

to keep an open mind and not harbour foregone conclusions, we can't know for sure whether all

shamans practiced deception. Descriptions and studies of rituals and shamanistic demonstrations of supernatural powers certainly

do appear to have been steeped in tricks and illusions. Even without such things, the reasoning of showmen versed in the magical arts points in the same direction. Let's ask a conjurer before we re-write the laws of nature. I am not claiming deception in rituals is a negative thing, rather to the contrary. This is, in fact, the point I am trying to make. Slight of hand and illusions are perfect tools to amplify emotional states in crowds. Real or not, the effects are powerful, and their impact on those participating in the rituals are real enough.

The fact that deception has been involved might bring the modern reader disappointment, we can’t seem to see any validity in something known to be fake. This is perhaps the foundations for much of religion and society's obsession with literalism. How can I believe anything, or take anything good from the bible, if its claims that the bat is a bird, or that evolution never happened, are false?

The fact that deception has been involved might bring the modern reader disappointment, we can’t seem to see any validity in something known to be fake. This is perhaps the foundations for much of religion and society's obsession with literalism. How can I believe anything, or take anything good from the bible, if its claims that the bat is a bird, or that evolution never happened, are false?

“The seemingly alien conjunction of belief and disbelief may well be quite standard human behavior. It happens most frequently in situations of make-belive. All the arts – performing, liteary, visual – offer the state of make-believe that transcends the opposition of belief and disbelief. Religion has always done it very well indeed.” Robert E Neale.

A whole lot

of our world's quarrels and disputes today, and throughout all time, has come from

confusing levels of reality. Human beings are symbolic creatures. We engage

emotionally in stories and find them fascinating and moving even if we know

they are untrue. Whether something is factual or not, whether or not it happened to someone at sometime, does not lessen our experience of a story

well-told, or the deep emotional changes it creates in us. A fable told, a fairy

tale enjoyed, or a myth recounted to cast light upon a difficult question, can

indeed enlighten the listener regardless of whether the animals in the

stories actually formed a band, or the Pied Pieper of Hamlin actually drowned an

entire town's children. The importance and value of such stories does not lie

in their exact wording. It does not matter that each telling differs, for a

literal interpretation of the stories are not their real wisdom. The truth lies in their symbolic meaning.

Confusion

of the symbolic level of reality with the literal or factual always brings

negative consequences. Think only of money. A famous anecdotal Cree Indian

saying reminds us:

“Only after the last tree has been cut down.

Only after the last river has been poisoned.

Only after the last fish has been caught.

Only then will you find that money cannot be eaten."

Only after the last river has been poisoned.

Only after the last fish has been caught.

Only then will you find that money cannot be eaten."

It is

important to be able to distinguish what’s real from what isn’t. Knowing what belongs in the literal/factual world, and what belongs in the symbolic world, has been a necessary skill at all times. Important for survival both literally and socially. Failing to do so is frowned upon as deception, lie or madness.

In the shadow lands between real or not, with one foot firmly planted in each world, we find religion, superstition, art and showmanship.

In the shadow lands between real or not, with one foot firmly planted in each world, we find religion, superstition, art and showmanship.

We have spaces designated

for suspension of disbelief. Spaces that Mircea Eliade calls sacred, as

opposed to profane, or ordinary, spaces. Sacred spaces are places

whit their own sets of rules and where a different . Normal logic and precaution can be left behind, for

inside these spaces it is safe to take a leap of faith into the absurd.

We have spaces designated

for suspension of disbelief. Spaces that Mircea Eliade calls sacred, as

opposed to profane, or ordinary, spaces. Sacred spaces are places

whit their own sets of rules and where a different . Normal logic and precaution can be left behind, for

inside these spaces it is safe to take a leap of faith into the absurd.Is it real or not?

The carnival is a place where whether something is real or not simply doesn't matter. Here the truth of life is lies least of all in facts. Within the carnival’s perimeter fences leaps of faith are expected and safe.

This is signified by the carnival high diver atop a thousand foot ladder swaying in the warm summer night. Perched precariously on a little platform far above the carnival lights he stands, and as we see him we know that everything we have learnt about the outside world tells us; if this man jumps, it will end in certain death. Yet still he jumps, and as he crashes into the shallow wooden pool below and triumphantly, death-defiantly, and dripping wet re-emerges, we understand with our hearts and our minds that the Carnival is a symbolic place where different rules apply.

No comments:

Post a Comment